Introduction

Welcome to a new chapter in the Chronicloud series, specifically one of the last articles about Azure Local, where we’ll discuss Redundancy. Initially, I wanted to include both backup and disaster recovery in this post, but as I started writing, I realized it was getting huge and unwieldy. Therefore, I decided to separate those topics into their own dedicated article.

The subject of redundancy tends to be tricky when talking with clients, not because they lack interest, but because the complexities and limitations can be daunting. This article might be more technical than usual, so if you’re unfamiliar with any terminology, please reach out to me directly (LinkedIn is great) and I’ll be happy to clarify the concepts.

Because I’m based in Germany, most customers here love having multiple physical data center locations separated by firewall walls, fully independent “rooms” that can operate if one site goes down. This naturally leads to a desire for multi-location redundancy. In the past (with Azure Stack HCI 22H2), that wasn’t a major problem if you only had two sites and no AKS, because a Stretch Cluster could usually do the trick. But with Azure Stack HCI 23H2 (now Azure Local), the integrated Resource Bridge doesn’t support Stretch Clusters, and that has changed the redundancy equation significantly.

In this post, we’ll tackle redundancy from several angles: nodes (physical hardware), storage, network and Active Directory. Let’s get started!

Redundancy

I’m splitting the redundancy discussion into three main parts:

- Nodes: Physical node redundancy in the cluster. For instance, if you have three nodes and two fail, you’ll see a potential loss of data and cluster availability.

- Storage: We’ll look at data resiliency on disks, such as how a two-node cluster might keep operating if one node fails, but if the remaining node’s single disk dies, data might still be lost.

- Other Infrastructure: Network design (no point having multiple nodes if everything relies on a single switch), multi-location data centers (e.g., rack-aware clusters) and Active Directory design (including why nesting domain controllers in the cluster can be problematic).

Throughout, I’ll do some rough capacity and resource calculations using 2 x 1 TB NVMe capacity drives plus 1 TB RAM per node, just as an example.

Redundancy of the Nodes

Talking about node redundancy means asking how many nodes a cluster can have (up to 16) and what happens when multiple nodes fail. In theory, if you have “half plus one” of the nodes functioning, and (or) you have a quorum (Azure File Share in the case of Azure Local), the cluster remains “operational”. However, that doesn’t guarantee that your storage remains accessible if the data resiliency requirements aren’t met, which is especially true with three-way mirrors in clusters of three or more nodes. If enough nodes go down simultaneously, data could become inaccessible or lost.

Personally, I’m not a huge fan of clusters with more than five nodes for Azure Local. The reason is that Storage Spaces Direct (S2D) can handle only so many simultaneous node failures while still keeping the data intact, and I prefer to keep things simpler. Let’s walk through some typical node counts:

One Node

You can technically run Azure Local with just one node. But it isn’t really a “cluster” since you have zero redundancy. If that single node fails, so does your entire environment. This setup might be simple in terms of CPU/RAM/storage planning, but I wouldn’t recommend it for any production environment that needs high availability. Even a minor node failure or an update problem can lead to downtime that’s tricky to fix.

Two Nodes

A two-node cluster gives you basic redundancy. If one node dies, the other automatically takes over the workloads, provided you haven’t over-allocated RAM and CPU. For example, if each node has 1 TB of RAM, you might be tempted to run workloads totaling 2 TB of RAM (like 2 VMs with 700 GB RAM allocated). But in a node-failure scenario, you only have 1 TB left to run everything. You’d see workloads failing to start if they collectively need more than 1 TB.

Overcommitting CPU also has consequences. If you had a 1:3 ratio (physical CPU : vCPU) across both nodes, losing one node means your ratio effectively doubles for the surviving node, possibly halving performance. But at least the cluster remains functional.

Three or More Nodes

With three nodes, you can leverage three-way mirror resiliency for your data, which allows the cluster to keep running if one node fails, even two nodes can fail in clusters that have more than 3 nodes and data still be safe. But if you run out of “mirrored copies” across multiple failures, data can be inaccessible or lost.

Another consideration is resource usage. Suppose each node has 1 TB RAM and you have workloads requiring 2 TB in total, distributed across the three nodes. If one node fails, you have only 2 TB left across two nodes. But if each of those two remaining nodes is already using a large portion of RAM, certain VMs might not be able to start. This is why you need an overprovisioning plan (or “failover capacity plan”) to handle node failures gracefully.

With bigger clusters, more resources are available for workloads, and you get more “hardware-level” redundancy. But S2D is generally tested up to losing two nodes simultaneously. If a third node also fails, you could run into data integrity issues, even though the cluster might still appear to have a majority for quorum. That’s one reason why I tend to keep my Azure Local clusters within a modest node count (like 2 to 5).

Redundancy and Resiliency in the Storage

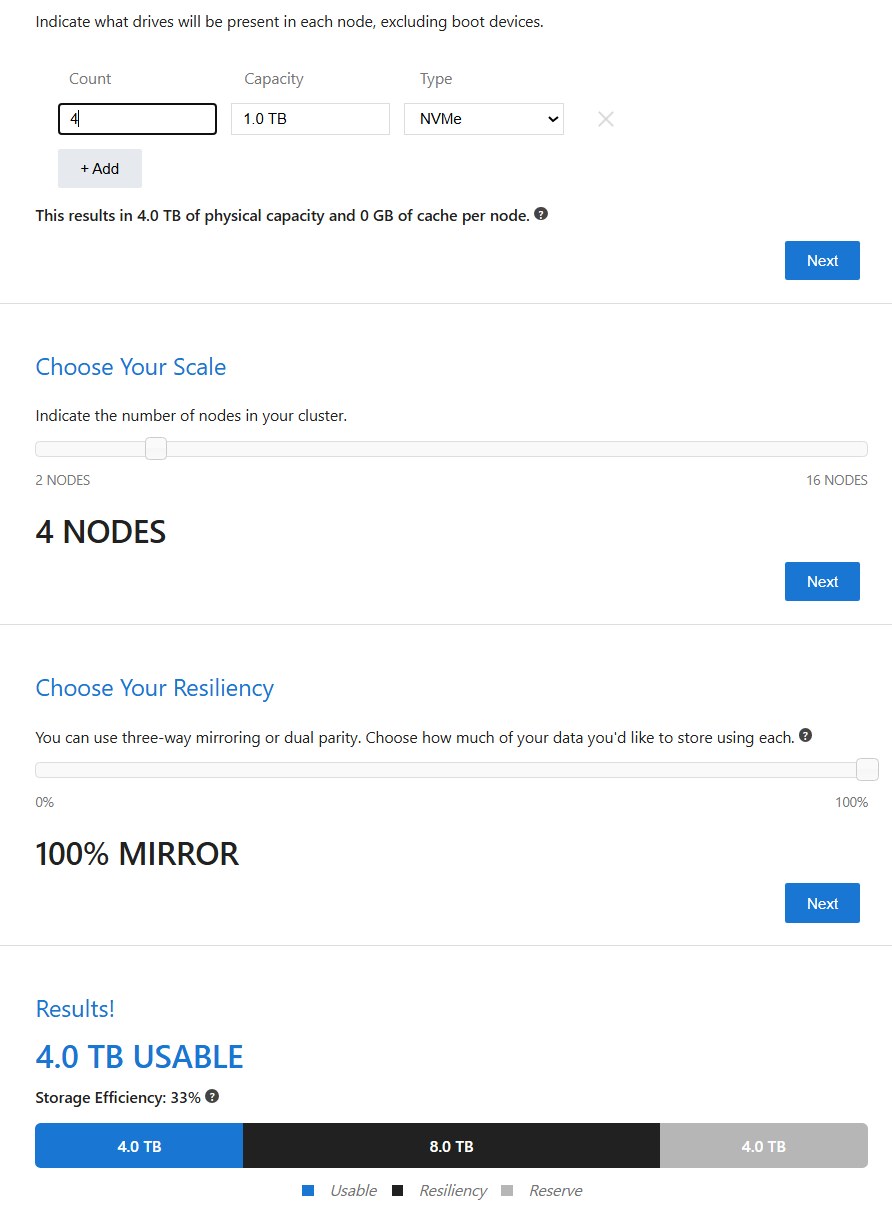

For raw vs. usable storage capacity calculations, I use the S2D calculator by Cosmos Darwin (LinkedIn): https://aka.ms/s2dcalc

Important: Azure Local requires a minimum of two capacity drives per node (hardware requirements). For two nodes, you’ll generally have a two-way mirror, and for three or more nodes, a three-way mirror. All nodes should have the same number of disks (same capacity and model).

Two-Node Cluster

A two-node cluster with a two-way mirror ensures that if one node fails, the other still hosts the data. When the failed node is restored, the system automatically re-syncs the data. This re-sync can take minutes or hours depending on network bandwidth, RDMA configuration (RoCE/iWARP), and the amount of data that needs to be copied back.

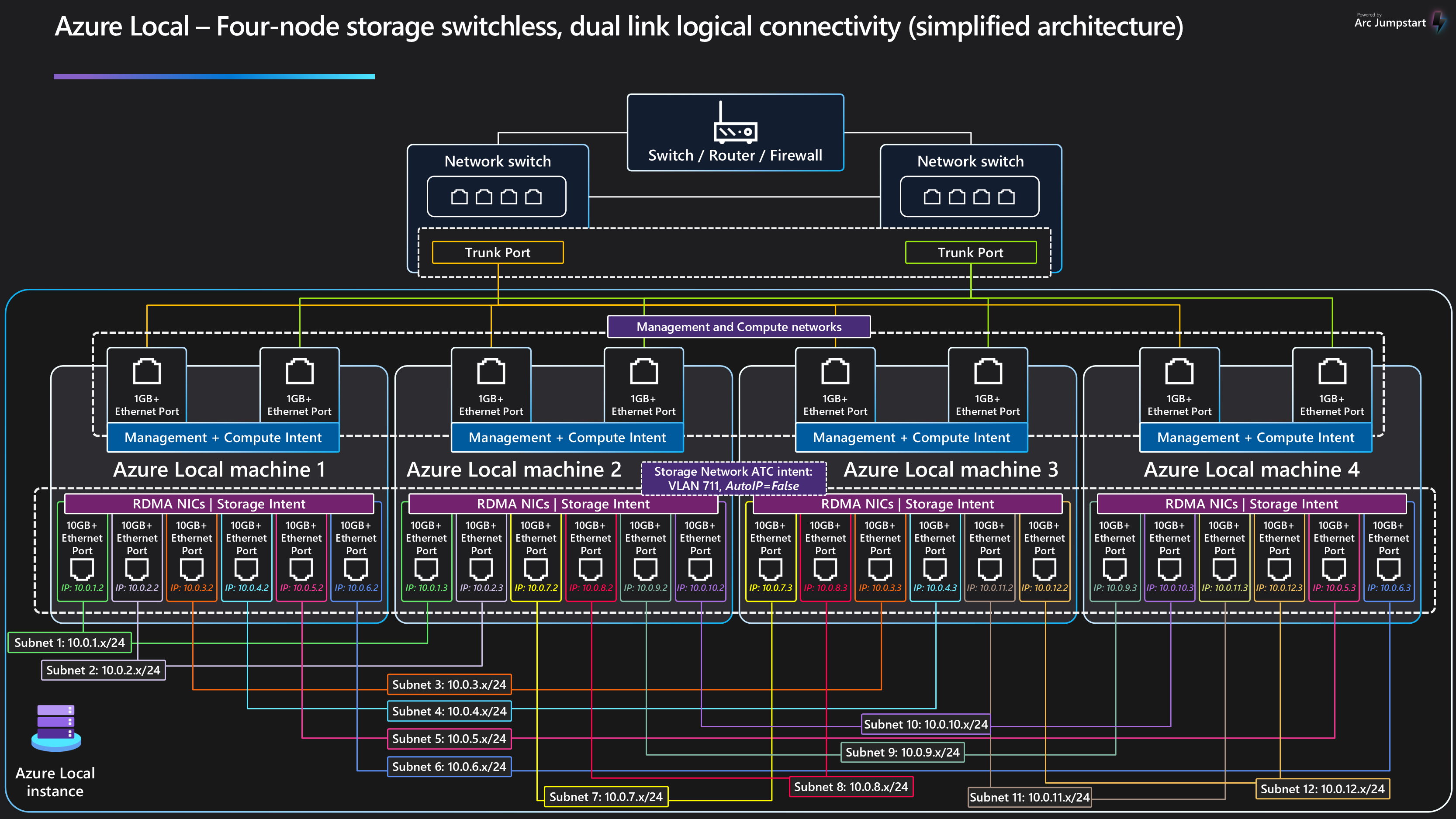

If each node has two 1 TB NVMe disks, that’s 4 TB raw total. However, because it’s mirrored, you only get about 1 TB of usable capacity:

Four-Node Cluster

With four nodes, you use a three-way mirror. This means data is replicated across at least three different nodes, so you can survive up to two node failures at once without losing data. But if a third node fails, you risk losing data consistency.

Re-sync times also get longer with more copies to rebuild. In extreme scenarios involving enormous data volumes, re-syncs could take days, though in my experience it’s usually hours at most. It depends heavily on your network speed, RDMA adapters, and switch capacity.

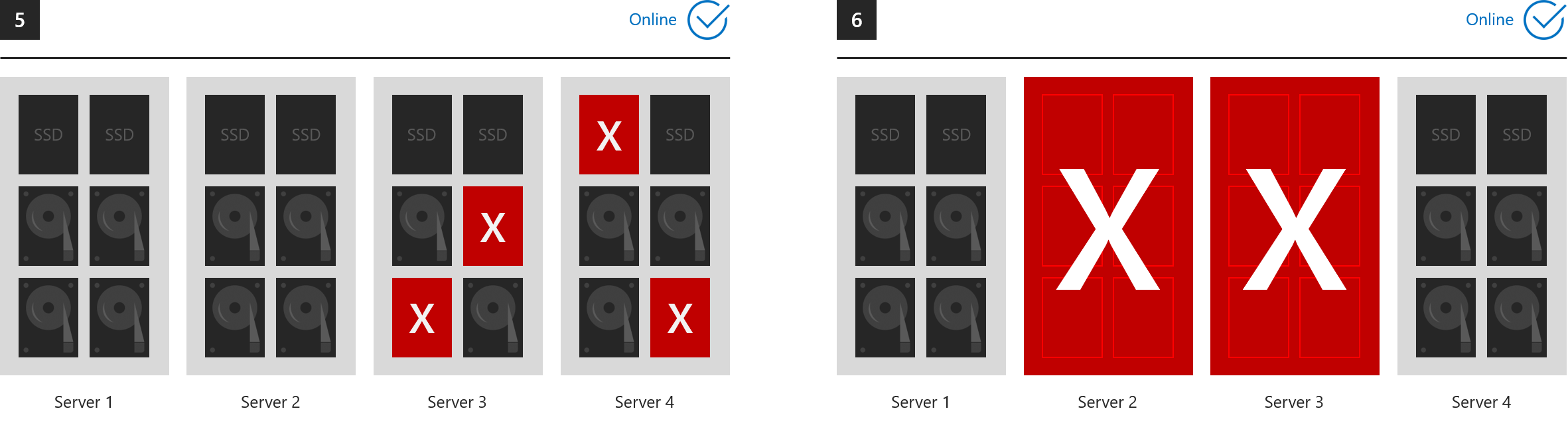

Microsoft’s fault tolerance documentation for S2D (like this link) provides some scenarios:

-

Situations where everything stays online (losing more than two drives but at most two servers):

-

Situations where everything goes offline (drives lost in three or more servers at once, or losing three nodes simultaneously):

For example, four nodes each with 4 x 1 TB capacity disks gives you 16 TB raw, but effectively only 4 TB usable under a three-way mirror:

Volume Counts: It’s best practice (see Microsoft’s volume planning guidelines) to match the number of volumes to a multiple of the number of servers. For four servers, create four volumes if you want balanced performance. Each node can “own” one volume’s metadata orchestration.

Other Redundancies in the Infrastructure

We can’t ignore the rest of the infrastructure that supports Azure Local, such as network design and Active Directory architecture. Let’s briefly discuss these points:

Network Redundancies

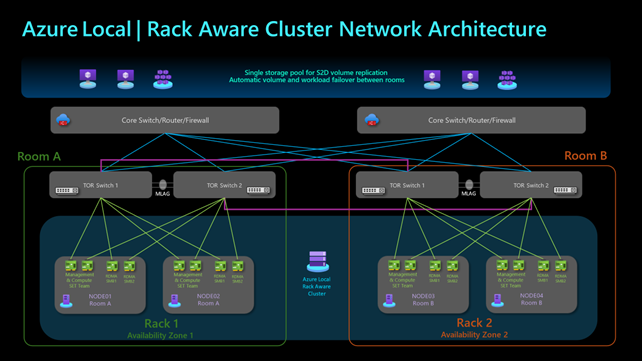

You can handle Azure Local networking in multiple ways. Some designs feature a dedicated storage switch (especially if you have more than four nodes). You might also want to split nodes across physical data center “rooms,” but official multi-site or campus-cluster setups are currently not supported (“Rack Aware Cluster” is in private preview).

Switches

Well, it depends on the number of nodes, your storage traffic design, and your budget. But you always need at least two switches for management and compute traffic. A single switch would act as a single point of failure, nullifying your otherwise redundant cluster design.

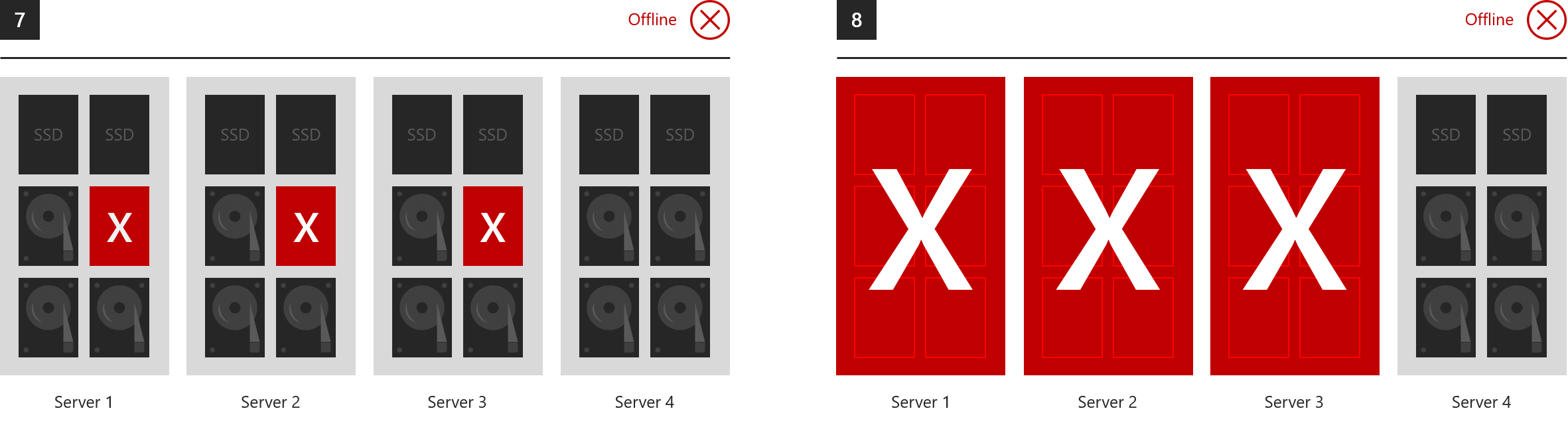

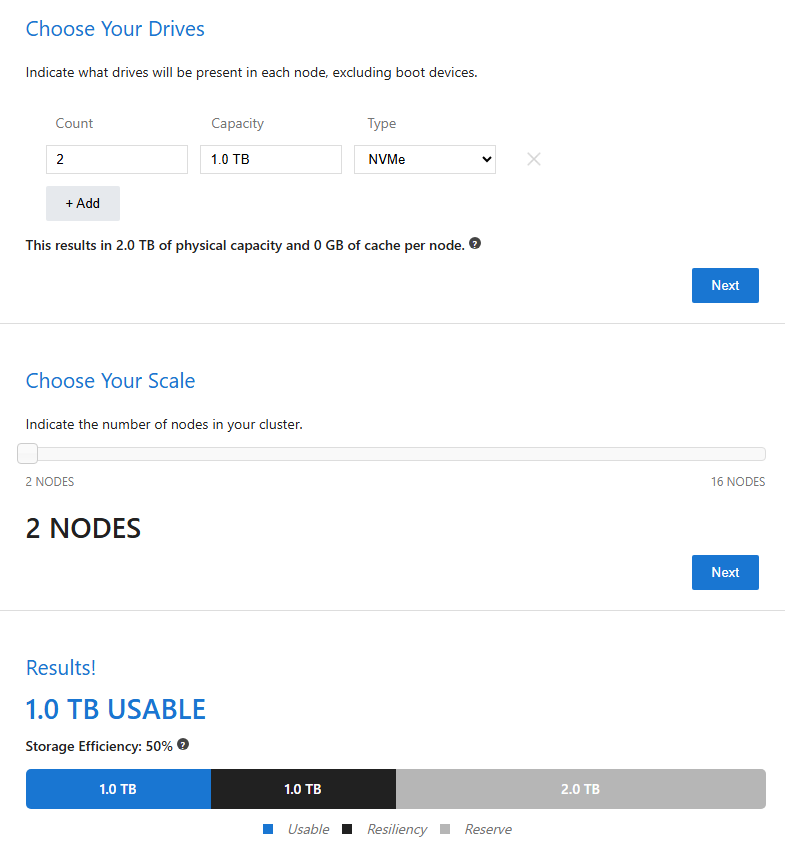

For up to four nodes, you can technically go switchless (often called Direct Attach) for the storage network, meaning the nodes are cabled directly to each other. I recommend RDMA (especially RoCEv2). This setup ensures that if one node fails, the remaining ones maintain inter-node connectivity. Personally, though, I consider switchless challenging beyond two nodes, it requires precise configuration, can be tedious to implement (via ARM templates), and is not very flexible (you can’t easily add new nodes or modify them without major rework). Its one advantage is cost savings if your existing switches can’t handle RDMA traffic. For reference, here’s a link describing that setup in detail: Four-node switchless, two switches, two links

And here’s the official diagram for that cabling method (props to whoever created it!):

In the image, each node has two connections to its neighbors, using six total network ports exclusively for storage. Because most network cards have two ports, you wouldn’t want to use both ports on a single NIC card to connect to the same node. If that NIC card fails, you’d lose the connection to the node entirely. Additionally, note that you can’t easily expand beyond two nodes in a “switchless” scenario, the only supported move is from a single node to a two-node cluster. Anything above two nodes requires a switch, as explained here.

Multi-Location or Rack Aware

After deciding how many switches to use, you also need to determine how many physical “locations” your cluster needs, e.g., is it all in one data center room, or multiple? Those familiar with the product already know this, but newcomers might be surprised to learn that Azure Local (starting 23H2) doesn’t support stretch clusters, meaning nodes should theoretically be in the same rack. I’ll mention a new way to set up Azure Local for two locations (really just two rooms in the same building) called Rack Aware Cluster.

In previous versions, you could configure a so-called stretch cluster for two sites, provided your round-trip latency didn’t exceed 5 ms (see Microsoft docs). However, that’s now invalid because Azure Local 23H2 includes new cluster management elements (like Azure ARC Resource Bridge) that don’t support stretch clustering. In my opinion, there’s also no real need to expand clusters this way because Azure Local is more of an Edge Datacenter solution, not a typical “full” data center approach. If you want balanced infrastructure across two sites, Windows Server 2025 might be a better option, or you could split Azure Local into two separate clusters.

Nevertheless, there is a future possibility (currently in private preview) to meet this need, known as Rack Aware Cluster (TechCommunity article). This upcoming feature may include up to eight nodes (four per side). Its advantage is that it could support the ARC Resource Bridge because the nodes reside in the same Layer 2 network. If I ever get the chance, I’ll test it once a public preview is available. For now, we only have a network diagram:

Active Directory Redundancy

In my opinion, the most controversial part of designing a new Azure Local environment is Active Directory, mainly because there’s no official best-practice guidance covering it. Starting with Azure Local 23H3, you can integrate Azure Local into your existing Active Directory with minimal effort by following the prep steps in this Microsoft doc. Those steps outline the prerequisites for registering Azure Local and creating the cluster. The question is: Do I use my current corporate AD (with all existing data), or do I spin up a separate AD domain (often called the Fabric Domain) just for Azure Local?

Unsurprisingly, the answer is: it depends, it depends on the management model you want and how you plan to operate the cluster. However, in the majority of cases, I recommend creating a dedicated Active Directory domain for Azure Local, so you avoid unexpected permission issues or admins deciding it’s a great idea to apply random GPOs to the solution (I’ve seen some downright bizarre situations arise that were very tough to fix afterwards! 🤣)

Keep in mind that if you create a new Active Directory, it isn’t strictly required to integrate workloads like AVD or AKS. The users relying on those services and the workloads themselves, base their authentication on Entra ID (and, in terms of network, you can just set VLANs to point to whatever domain controllers they specifically need). You should also remember that Azure Local can be managed through Azure RBAC in the portal, making dedicated Fabric Domain accounts largely unnecessary. For now, as long as Azure Local still requires some form of AD domain (the version without AD is apparently coming later this year), my personal recommendation is to stand up a dedicated AD domain for Azure Local.

So, once you decide you want a new AD domain, where do you host it? One possibility is to run a domain controller for that new Fabric Domain in a VM outside Azure Local (for example, in your existing infrastructure or even on a laptop if you’re brave 😜). Then you register Azure Local with Azure and add a second domain controller inside the cluster itself. A frequent question is whether you can nest both DCs in the cluster. Theoretically and practically (if we’re being honest), yes (but you shouldn´t), you can migrate the domain controller you used to register Azure Local into the cluster. The problem arises if there’s a cluster wide outage. The cluster tries to start up, but both domain controllers are also part of that same cluster (even the storage!). You hit the classic chicken-and-egg scenario: the cluster can’t come online because there’s no AD available, and AD can’t come online because the cluster is offline.

Because of this, my one ironclad piece of advice is that no matter what you do (new domain or existing domain), ensure that at least one domain controller remains outside the cluster and is configured as DNS for the cluster. You can nest the second domain controller in the cluster without issue, or even migrate it in as an ARC VM. (We’ll talk more about that migration flow in future articles.)

Conclusion

Although I shortened some sections, I think this article still provides a clear (and somewhat “simple”) overview of what to consider when designing Azure Local with redundancy in mind. I had to omit backup and disaster recovery to avoid tripling the size, but those will be covered in the next post.

The best advice I can give is: if you’re new to Azure Local, reach out to a trusted consultant or your OEM for guidance before diving in. If you’re set on going solo, join the Azure Local Slack channel and clarify any doubts first. It’s easy to paint yourself into a corner if you’re not aware of certain limitations.

Thank you for reading all the way through! If you have any questions, feel free to ping me on LinkedIn. I’m always happy to help clarify or share insights from my experience.

Comments